Bubble, But for How Long?

The current scenario of higher asset prices during a recession has one logical conclusion – we are in a bubble. The question is, when will it burst? As part of their January commentary, Alfred Lam, Senior Vice-President and Chief Investment Officer, and Marchello Holditch, Vice-President and Portfolio Manager, CI GAM | Multi-Asset Management, look at what factors are driving asset prices higher and why central banks may be hesitant to let the bubble burst.

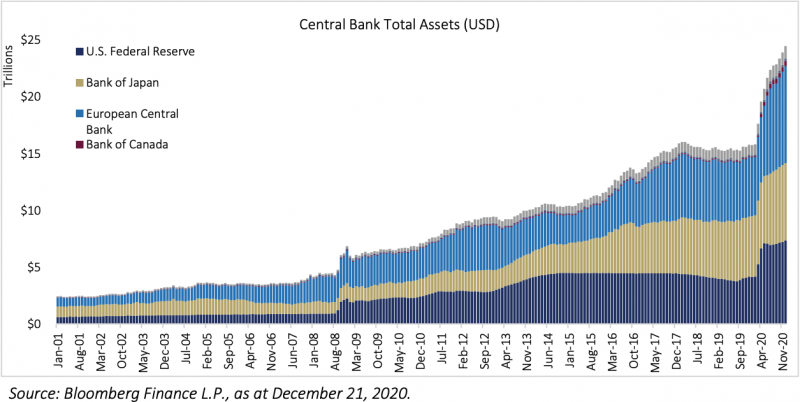

Without a doubt, 2020 was a “loss” year. Individually, we lost the ability to live our normal way of life. Globally, currencies lost their purchasing power as central banks added US$9 trillion to the system (leading to price increases in almost everything, including stocks and properties), and over 1.8 million people lost their lives due to COVID-19.

It is fair to say that the current scenario of higher asset prices during a recession is not normal. The natural conclusion is that we are in a bubble, and we do not disagree. However, it is not a typical bubble where the issue is price speculation in a single asset. Rather, this bubble formed due to increased central bank balance sheets (or money supply). From 2011 to 2020, central banks printed approximately US$17 trillion, and half of that is attributed to 2020 alone. Imagine a transaction where someone is selling an asset and getting currency in return. The seller then demands more units of currency in exchange as the currency supply has dramatically increased, even though the asset supply has not changed and demand may have slipped.

Expanding for longer?

The question is, when will this bubble burst? In other words, when will central banks shrink their balance sheets? Expanding is usually an easier decision than shrinking, as decreasing money supply has the opposite effect of lower asset prices, which is typically perceived as negative. Unless we have a very strong economy to offset, then this is usually the last thing on policymakers’ minds. Using history as a guide, central bank balance sheets last peaked at US$16.0 trillion in 2018. With effort, mainly by the U.S. Federal Reserve, that balance fell to US$15.2 trillion in 2019. You may notice the reaction to reduce spending was extremely slow compared to the growth since 2008.

With interest rates already at or close to zero, central banks have aggressively used money supply as a tool to combat the market disruption brought on by the pandemic, similar to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008- 09. Policymakers seem very comfortable leaving the bubble as is, and most of us are not complaining as higher prices is not a problem for investors. However, this doesn’t mean economies are growing rapidly. Rather, the wealth gap is widening in favour of those who own assets.

For example, inflation – as tracked by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which measures changes in consumer prices – has been mild over the last decade. However, we believe the basket of data used to calculate CPI does not accurately capture the inflation of assets such as real estate. According to CPI, prices have grown at an average annual rate below 2% over the last 10 years, but Toronto real estate has gone up by more than 8% per year over the same period. Potential homeowners have effectively been priced out of the market because they do not own inflated assets to sell and they cannot save enough to keep up with the rapid price increases of real estate. As a result, asset owners become wealthier, while those with little net worth fall further behind. That being said, we believe central banks are still likely to focus on boosting prices for the “majority” of the population. This means, the large increase in money supply and renewed currency debasement could continue for years if not decades to come. While unfair, it is not up to us to decide.

What to do in unusual market conditions?

While central banks are aggressively printing money, we believe being defensive and “hiding cash under the mattress” is a losing strategy. Over the last few months, our goal has been to protect our investors’ purchasing power in these very unusual market conditions, and we have actively deployed cash and trimmed government bond holdings for larger equity exposure. As always, we continue to monitor market conditions and may from time to time cut back on our equity exposure to manage downside volatility.